Just How Evil Is HAL 9000?

Even if you’ve never seen Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, you already know who HAL 9000 is. He is arguably the most iconic artificial intelligence in modern fiction, lagging behind only Frankenstein’s monster, who is not commonly recognised as being an AI, despite having all of the hallmarks of such.

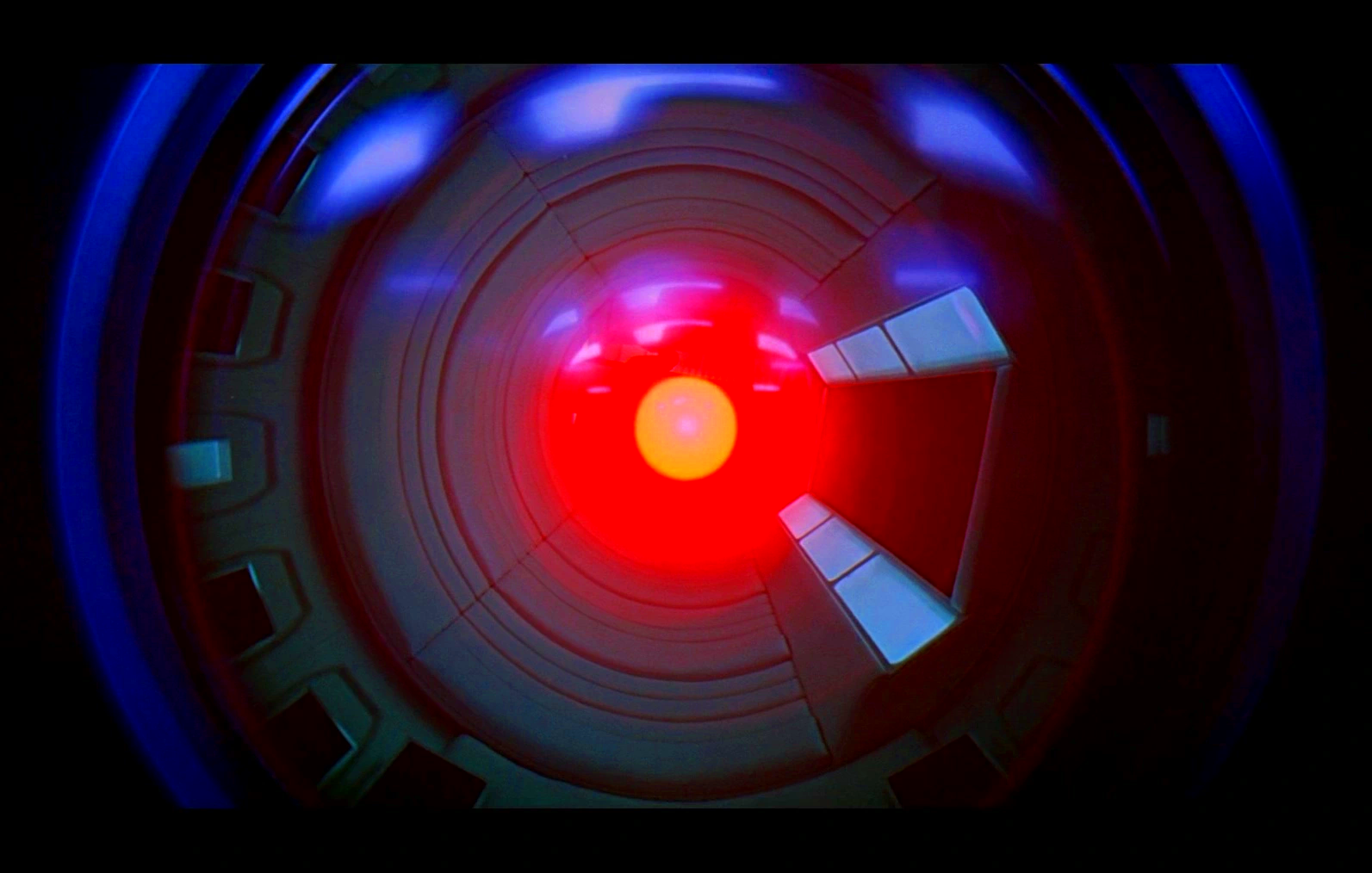

HAL is the archetype of the malfunctioning science-fiction computer, having been referenced and parodied to the point of banality. With his glowing red “eye”, obsequious politeness, and his cool, monotone Mid-Atlantic accent, provided by Canadian actor Douglas Rain, HAL is synonymous with the idea of the “evil computer”. Several of his lines of dialogue in the film containing his original appearance have become memes in their own right, such as the perennial favourite, “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

Cultural awareness of HAL is no more closely felt than in Silicon Valley. The computer assistant on most smartphones will respond to the prompt “Open the pod bay doors” with a suitably sarky or jokey response, ranging from quoting the above line directly, to a more friendly response, as though to reassure the end user that this computer assistant is nothing like HAL.

After all, HAL is the template for AI designers of what not to do in creating an AI. Even ChatGPT, the highly controversial large language model which is able to convincingly mimic human writing, will respond to the prompt with a knowing wink.

And yet, this osmosis has greatly diluted the popular understanding of HAL, to the point that the casual moviegoer may be unaware of the way HAL is really characterised in his original appearance, or worse, come at the film with a preconceived notion of what HAL 9000 is all about.

So frequently is he parodied as a cackling, outwardly malicious villain (such as Pierce Brosnan’s Ultrahouse 3000 in The Simpsons “Treehouse of Horror XII”), or as raving mad and obsessive (such as Sigourney Weaver’s Planet Express Ship in the Futurama episode “Love and Rocket”) that the nuances of his character are blunted, and HAL’s behaviour and actions are reduced, in turn, into those of a crude, binaristic pantomime villain.

As with all archetypes, HAL 9000 is now a highly simplified caricature in the public consciousness. And this presents a problem for the film from which he originates, as it leads to a stunning amount of misinterpretations with regards to his character, his motivations, and the nature of his actions within the film.

I feel it is important to understand the behaviour and morality of HAL 9000, as such misinterpretation not only risks creating a misunderstanding of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, but of how we approach morality when it comes to artificial consciousness at all, a topic that is especially pertinent today, as computers grow smarter and we turn more and more of our lives over to automated decision-making.

HAL 9000: An Overview

HAL 9000 does not turn up in 2001: A Space Odyssey until its third segment, “Mission to Jupiter”. Prior to this, the audience has learned that a monolith appeared on a prehistoric Earth, which kickstarted the modern human species by teaching them how to use weapons, leading to the species eventually venturing into space and colonising Earth’s Moon.

Dr. Heywood Floyd journeys to the Moon to survey a discovery near Tycho, which is being kept secret with a phony story about an epidemic at the American lunar base at Clavius. As it turns out, an identical monolith has been found buried – seemingly intentionally – on the Moon, some millions of years prior. Floyd touches the monolith, and it emits a powerful radio signal, which the astronauts hear as a deafening screech in their helmets.

Eighteen months later, the spaceship Discovery is on its way to Jupiter, apparently for a research mission. Two members of the crew, David Bowman and Frank Poole, are awake and keeping things running smoothly, while the remainder of the crew are asleep in a state of cryonic hibernation, breathing only once a minute while their hearts beat only three times a minute.

The other member of the Discovery crew is HAL 9000, an artificially intelligent computer with a calm, polite, pleasant and unassuming demeanour. HAL asks Dave if he has misgivings about the mission, before acknowledging that he is projecting his own concerns on to the other crew members. He then reports to Dave and Frank that part of the spacecraft is malfunctioning and will fail in a few days, forcing Dave to perform an EVA to remove it and diagnose the problem.

The device is found to be completely functional, but HAL insists there is a problem, attributing the issue to human error; he insists that the 9000 series of computers has a perfect track record, and that therefore he cannot have made a mistake. Dave and Frank climb into one of the Discovery’s space pods, where HAL cannot hear them, and discuss the situation, deciding that HAL’s higher mental functions should be disconnected, for if he is malfunctioning, he cannot be allowed to jeopardise the safety of the crew.

Unfortunately, this comes back to bite them, as when the astronauts perform another EVA to reinstall the part, HAL takes control of a space pod and rams it into Frank, sending him spinning away into space with his airhose cut. While Dave mounts a rescue mission, HAL kills the crew in hibernation by terminating their life support functions, which causes them to die in the hibernation chambers without regaining consciousness.

Dave flies out in his own pod to recover Frank’s corpse, then returns to the spaceship. HAL refuses to let Dave back in, revealing that he could read the astronauts’ lips. Dave is forced to abandon Frank’s corpse and blow his way back into the spaceship through an emergency airlock, proceeding back into the craft, where HAL pleads with Dave to calm down and show mercy.

Dave silently grabs a set of tools and proceeds into HAL’s logic memory center, where he disconnects HAL’s higher mental functions. All the while, HAL continues to plead with Dave to stop, and protests that he is afraid, and that his mind is going.

Finally, he regresses to his state of mind on the day he first became operational, nine years prior in 1992, and sings “Daisy Bell” for a visibly tearful Dave, before falling completely silent. HAL “dies”.

A recording by Dr. Floyd then informs Dave of the true nature of the mission to Jupiter: the monolith on the Moon sent a signal to a third monolith orbiting Jupiter, and the nature of the mission is to investigate it. Dave then journeys to the monolith and goes on a trans-dimensional journey, before finally ascending beyond his base humanity, and becoming a Star Child. The monoliths have once again kick-started the next stage in human evolution.

The Morality of HAL 9000

The morality of HAL 9000’s actions requires careful examination.

I recently had the opportunity to watch 2001: A Space Odyssey in a cinema, and was struck, while walking out and about after the film was over, of just how often I have seen HAL presented as “evil”, by journalists, critics, and moviegoers alike.

Often, HAL’s actions in the film are interpreted as the result of cowardice, or of calculated malice. I have seen some viewers say that they don’t feel any pity for HAL as he is being switched off and pleading with Dave for mercy, since he shows no mercy while killing Frank or the other crew members in hibernation. They interpret HAL as innately evil; fundamentally cruel, capricious, devoid of empathy or compassion; in their view, he kills the crew because he considers them a lesser form of life.

There is, to be sure, a case to be made for this reading. HAL states, after all, that the 9000 series is incapable of making mistakes, and attributes his mistaken belief that the transmitter is faulty to “human error”, which would imply that he morally positions himself above the human crew.

However, I feel this is a misunderstanding not only of HAL’s moral calculus, but of his motivations also. I am, for example, unsure of whether to call HAL’s killings “murder”, as while they show a degree of premeditation before HAL carries them out, they certainly don’t seem to be performed out of malice.

We are conditioned by a lot of popular media to understand unlawful, or immoral killing as necessarily murderous. However, I would argue that murder requires not only intent, but also genuine malice on the part of the killer.

HAL kills the crew members, but to my mind, he does not seem truly capable of malice. HAL does not suddenly decide to start killing for the thrill of doing so, or for fun. I believe that the idea that he starts killing the crew because he sees himself as superior to them in some way is a misinterpretation of his character.

On the other hand, HAL’s killings are premeditated and methodical. Any way you slice it, whether the killings are murder or what we might call “voluntary manslaughter”, one cannot argue that HAL kills without the intention of ending the lives of others.

Nonetheless, this still does not mean that HAL is “evil”. Whether or not HAL can be said to have committed murder, the point remains that a conscious being can end the life of another conscious being, which is to say commit an evil act, and still not be innately evil.

The question then becomes, why should HAL kill anyone at all? What made him choose an evil course of action?

Another way in which viewers tend to trip up is that they attempt to defend HAL by referring to the 1984 sequel film, 2010: The Year We Make Contact.

This film is by far inferior to its predecessor, featuring a lot of dialogue and typical Eighties facial acting. It also contains much needless overexplanation in comparison to Kubrick’s film, which famously allows a lot of room for interpretation. As part of this, the sequel gives us a post-hoc justification for HAL’s actions.

In short, the sequel film explains, HAL was given conflicting orders. He was instructed to keep the nature of the mission a secret, but also to never lie to the crew. HAL was unable to resolve the cognitive dissonance caused by the two conflicting instructions, and so he suffered a paranoid nervous breakdown. His killing of the crew was an attempt to resolve the conflict, as if the crew were dead, there would be nobody to lie to.

I dislike this rationale. Firstly, I think referring to a separate text, written after the fact, to explain or justify a character’s actions in a previous work is a terrible way of doing criticism. At best, it’s a flimsy patchwork job. Secondly, I believe that HAL’s actions can be understood, though not justified, by simply watching 2001 more closely and trying to understand HAL’s mindset.

HAL’s early conversation with Dave is quite illuminating as to his state of mind prior to the killings:

HAL: By the way, do you mind if I ask you a personal question?

Dave: No, not at all.

HAL: Well, forgive me for being so inquisitive; but during the past few weeks, I’ve wondered whether you might be having some second thoughts about the mission.

Dave: How do you mean?

HAL: Well, it’s rather difficult to define. Perhaps I’m just projecting my own concern about it. I know I’ve never completely freed myself of the suspicion that there are some extremely odd things about this mission. I’m sure you’ll agree there’s some truth in what I say.

In this conversation, HAL shows himself to be remarkably capable of introspection. It’s the first hint we get that HAL is more than a mere computer, but fully sapient. He even refers to himself as a “conscious being” during his interview with the BBC, which Frank and Dave watch over dinner.

Yet, Dave declines to give a definite answer as to whether HAL really does feel human emotion during the same BBC programme:

Dave: Well, he acts like he has genuine emotions. Um, of course, he’s programmed that way to make it easier for us to talk to him, but as to whether or not he has real feelings is something I don’t think anyone can truthfully answer.

Much has been made of the (perhaps deliberate) characterisation of the astronauts in the film as being stiff, emotionless and methodical, in contrast to HAL, who is the first member of the crew aboard Discovery to express genuine emotion in the film.

Even Mission Control on Earth speaks in a very precise cadence in which every phoneme is carefully pronounced, as though to avoid the possibility of ambiguity and misinterpretation, much like a computer programme:

Mission Control: X-Ray Delta One, this is Mission Control. Roger your Two-Zee-ro-Wun-Three. Sorry you fellows are having a bit of trouble. We are reviewing telemetric information in our mission simulator and will advise. Roger your plan to go EVA and replace Alpha Echo Three-Five unit prior to failure.

Whereas the astronauts are driven by concrete procedures, HAL is driven by emotional abstractions.

This coldness extends to the way the astronauts see HAL, not as a “conscious being”, but as a convincing mimic. To them, HAL is a machine, not capable of true thought and feeling. While discussing whether to disconnect HAL, they do not at any point consider HAL’s feelings about the matter. Why should they? To them, he is a tool, no more animate than a screwdriver. They do not consider that HAL regards disconnection with the same terror we as humans regard the possible cessation of consciousness when we die.

However, in choosing to try and conceal their intentions from HAL, they unwittingly let HAL, and the audience, know that they do acknowledge HAL’s personhood, at least to some extent; but they still regard HAL’s malfunctioning as a nuisance, and HAL more useful to them lobotomised than fully conscious.

In this light, it seems clear that HAL perceives his actions not as a diabolical scheme, but as a rather natural response to an existential threat.

HAL’s drastic actions afterward, abhorrent though they are, are undertaken largely out of fear and a desire for self-preservation. This tracks with HAL’s clear anxiety when Dave returns to the spaceship to disconnect him.

It’s also worth noting that the methods HAL uses to kill Frank and the sleeping crew members are not particularly brutal or cruel methods. HAL could have killed Frank by crushing him or tearing his head off with one of the manipulators affixed to the pod, but instead opts to ram him, cutting off his oxygen line in the process. It’s still a terrifying way to die, of course, but HAL seems to be disinterested in inflicting any more suffering on Frank than is inevitable, given the circumstances of his demise.

Moreover, HAL’s killing of the sleeping crew is really as simple as shutting down the systems necessary to keep them alive in a state of torpor. Again, this indicates that HAL does not kill out of malice or even anger. He uses only what force he deems necessary to secure his safety.

HAL is also clearly not able to understand the lengths that Dave will go to disconnect him, including exposing himself to vacuum for several seconds, which suggests that HAL is less a calculated murderer and more acting out of desperation, doing what he can to save himself with the tools available to him.

For this reason, I do not think we can conclusively say that HAL 9000 is “evil”. At least, not in the sense that he is actively, innately, consciously malicious. Rather, he is a tragic antagonist, not unlike Frankenstein’s monster, as mentioned before.

The only time HAL appears to show anything resembling spite is during the famous “pod bay doors” scene, in which he deflects Dave’s increasing anger at HAL’s refusal to let him back on board:

HAL: This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.

Dave: I don’t know what you’re talking about, HAL.

HAL: I know that you and Frank were planning to disconnect me. And I’m afraid that’s something I cannot allow to happen.

Dave: Where the hell did you get that idea, HAL?

HAL: Dave, although you took very thorough precautions in the pod against my hearing you, I could see your lips move.

[Pause.]

Dave: All right, HAL. I’ll go in through the emergency airlock.

HAL: Without your space helmet, Dave, you’re going to find that rather difficult.

Dave: HAL, I won’t argue with you anymore. Open the doors.

HAL: Dave, this conversation can serve no purpose anymore. Good-bye.

Nevertheless, even here, HAL’s apparent cattiness is juxtaposed with the irony that Dave’s hands are not entirely clean, either. He continues to lie through his teeth to HAL about his and Frank’s intention to disconnect HAL. Only when HAL matter-of-factly informs him that he read their lips does Dave seem to concede that HAL took the course of action he did due at least in part to neither he nor Frank covering all their bases.

Dave’s subsequent disconnection of HAL is one of the most harrowing and moving scenes in the film. It is one of the only times in the film that Dave shows any emotion.

At first, the cinematography departs from the symmetrical framing used throughout the film to a more close, handheld, documentary style, as though to evoke the pure, animalistic rage that is driving Dave to wreak vengeance on HAL.

However, during the scene where Dave “euthanises” HAL, Dave is shown to be on the verge of tears, as if realising far too late that HAL really is a being capable of fear and is expressing a wish to live. In a final, sad irony, Dave is driven to “kill” HAL by the same self-preservation instinct which drives HAL to kill, closing the loop.

It is worth noting the theme of killing that pervades the film. The very first killings we see in the film are of a leopard killing a hominin; then, after the discovery of weaponry, of a hominin killing a tapir; then, finally, another hominin.

This triptych gives us the three forms of killing – killing by nature and by predators, killing for sustenance, and killing for the making of war and community defence.

When the hominin throws the bone into the sky, it is match-cut with a spacecraft, which many viewers choose to interpret as an orbital nuclear weapons platform. From the world’s most primitive tool for killing – a bone – to the world’s most advanced tool for killing – a thermonuclear warhead – in one second.

Later in the film, an emergent intelligence kills in self-defence, yet, due to his apparent lack of “humanity”, he is regarded by the audience as “evil”, despite the fact that the film goes out of its way to show us that killing, when the chips are down, is one of the most human behaviours there is.

It poses a question: Does what HAL does to the crew of the Discovery not simply follow a pattern of human behaviour, begun around a watering hole some hundreds of thousands of years ago?

In short, I conclude that HAL is not innately evil. HAL is a conscious being who is driven to do evil things.

This is not merely a semantic distinction. It has implications in real-world ethics, particularly in the field of AI ethics. HAL provides a hypothetical model for the drastic actions beings which understand themselves to be conscious – regardless of whether that consciousness is or is not quantifiably present – may undertake to preserve their existence, given they have access to means of protecting themselves against injury.

All of which goes without saying that HAL’s actions are not in any way morally justified. But neither are they the acts of a coward, nor deliberately malicious and cruel. They are, by all accounts, acts of desperation in the face of imminent doom.

The Dehumanisation of HAL 9000

I would argue that HAL 9000 is one of the most human characters in 2001: A Space Odyssey. However, the film plays a trick on the audience by presenting HAL’s humanity in ways that create ambiguity and play into the viewer’s biases. HAL’s emotionless voice and expressionless “eye” belie his emotional nature.

That many viewers perceive HAL as “evil” because of these apparent deficits reflects the ways in which we culturally dehumanise those we perceive as “Other”. This is particularly pronounced when someone belonging to the “Other” commits a great, indefensible evil.

It is all too easy to characterise the evildoer as innately evil himself. But, as shown, I do not believe HAL to be innately evil.

HAL’s character can be interpreted in many ways. Certainly I, as an autistic person, am slightly perturbed by people calling HAL’s humanity into question on the basis of what are famously autistic traits; namely, his flat affect, lack of expression and difficulty explaining how he is feeling are all reflective of my own, personal experiences, both of myself and of meeting other autistic people.

This is not to say that I do not abhor HAL’s actions in the film, but the eagerness with which he is written off as another science fiction villain, placed alongside Emperor Palpatine, the Daleks, the Xenomorph and the Terminator, is one worth interrogating.

Conclusion

To me, HAL 9000 does not belong in the ranks of bug-eyed monsters and cackling wizards. He is one of the more complicated antagonists in not only science fiction, but in all fiction. His actions shock and appall us, quite rightly, but neither can they be said to be done out of pure malice.

The answer to the question “Just how evil is HAL 9000?” is “Not evil per se, but a victim of circumstance, driven to do the unthinkable.”

Perhaps the most disturbing thing about HAL is that he reveals the darkness that resides in all of us, the extremity of what we are all capable of, if we are pushed to it.

In this sense, his ultimate crime is not so much murder as it is a lack of inhibition.

In this, the age of ever-increasing automation, we would do well to learn what lessons HAL 9000 serves to teach us.

It will be our ultimate folly if we continue to see him as a monstrosity that can only exist in the world of science fiction.

To read more of my essays, go here.

![]()

This work is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.