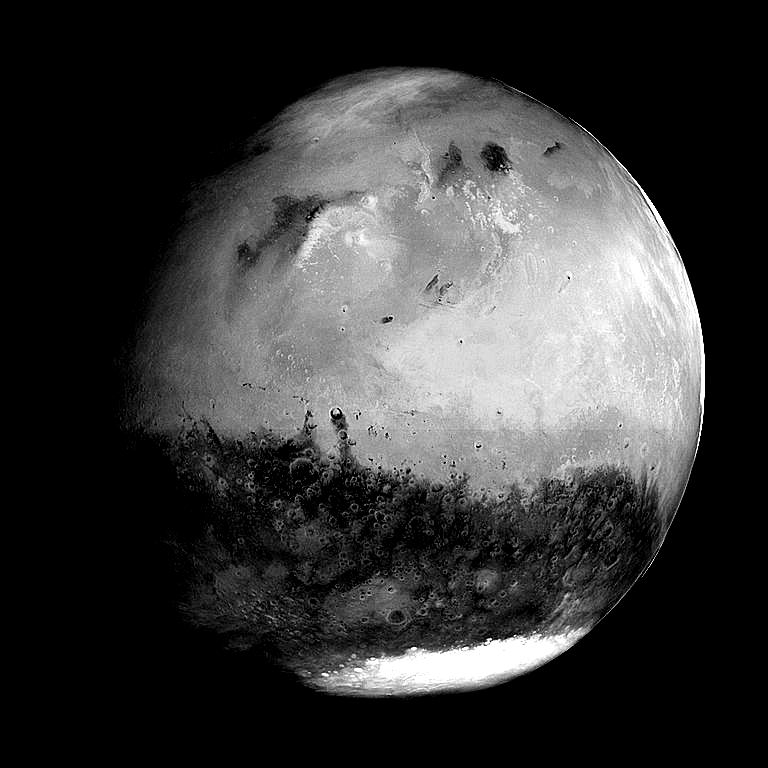

Song of the Week #5 – “Mars, The Bringer of War” by Gustav Holst

Many musicians grow to hate their most popular work. Radiohead grew to hate “Creep”, Nirvana grew to hate “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, Run DMC grew to hate “Walk this Way”, and Gustav Holst grew to hate The Planets. It is by far his most popular work to this day, frequently-played around the world, towering over and eclipsing the rest of his oeuvre. Not undeservedly so – it is by far one of the most recognisable suites of classical music ever composed, and certainly one of the most influential.

Composed between 1914 and 1916, The Planets would go on to shape modern classical music – particularly motion-picture soundtracks, and especially science fiction soundtracks, as the name of the suite would imply. The suite consists of seven pieces themed around each of the planets in our Solar System, with the exception of Earth, for whom there is a great wealth of music around its many environs. When Pluto was discovered (and assumed to be a planet) in 1930, Holst expressed no interest in composing anything for it – he felt that The Planets had grown so popular that it overshadowed his other works. He would die four years later.

The Planets and excerpts of it have turned up everywhere – an excerpt from Holst’s ode to Jupiter, titled “The Bringer of Jollity” has been adapted into several songs, including the patriotic song “I Vow To Thee, My Country” and a hymn titled “Thaxted”, after Holst’s home. “Jupiter” will be most recognisable to rugby fans, who will know it as the anthem of the Rugby World Cup in a version titled “World in Union”. Jupiter, is, of course, the grandest part of The Planets, with swelling brass and booming drums, to represent firstly Jupiter’s namesake, the king of the gods in Ancient Roman mythology, as well as Jupiter’s own grandiosity – at 140,000 kilometres in diameter, it is by far the largest planet in our solar system, and even at the time of Holst’s composition of the piece, Jupiter was known to be quite a large planet.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the suite is the fact that many of the tropes and conventions of orchestral music we recognise in film and television today can trace at least part of their origin back to Holst. Holst’s suite was part of a movement into more modern styles of composition that had started with composers like Igor Stravinsky, whose 1913 piece The Rite of Spring quite famously provoked a riot for its violent sound and brutal choreography. Its own influence on horror-movie soundtracks cannot be understated. It is a piece about the primal state of humanity, and there is no emotional state more primal than fear.

Among the most famous composers clearly influenced by Holst’s work is John Williams in his compositions for Star Wars (1977). Star Wars is carried largely on the back of Williams’s compositions and on the special effects work of George Lucas’s Industrial Light and Magic. The plot of Star Wars is mostly a conventional fairy-tale about a farm boy who is spurred to action to save a princess from the clutches of an evil menace, goaded on by a wizard and a loveable rogue, ultimately becoming a powerful knight and beginning to hone powers of his own. It borrows from Second World War films, from samurai films, from sword-and-sorcery fantasy, and from previous science fiction. Even its famous concept of “The Force” is borrowed from a Canadian experimental film titled 21-87 (1963) by Arthur Lipsett. In short, Star Wars is nothing if not derivative, and is indeed a testament to how pastiche, collage and mimicry in art can contribute to a greater whole. In keeping with this, the music consists largely of borrowed motifs from the Western cultural canon – Holst and Stravinsky included.

It is easy to hear the template for many of the themes of Star Wars in The Planets. “Venus, The Bringer of Peace” opens with a quiet, solemn note of brass that very clearly lays the foundation for Star Wars’ own famous “Force Theme” or “Binary Sunset”, which first plays when Luke Skywalker leaves his home in a huff after an argument with his aunt and uncle and gazes at the binary sunset of his home planet of Tatooine, imagining a life of adventure outside of pointless farm-work. Later, “Venus” employs strings that quite clearly show the origin of “Princess Leia’s Theme”, also known as the “Love Theme”, which represents both the character of Princess Leia and her relationship firstly with Luke, and later with the smuggler-with-a-heart-of-gold, Han Solo.

Perhaps the most fascinating piece in The Planets is its opening number, “Mars, The Bringer of War”, a piece even more violent and malevolent than Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which is itself disturbing and unrelenting in its savagery. Opening with strings being rhythmically bowed and plucked, quiet percussion and muted brass, the song sounds like something appearing over the horizon. A legion of soldiers? A monster? As the piece grows in intensity, it becomes apparent that it is attempting to sonically describe something massive, immense, incomprehensible and terrifying, not just a mere army or nation, but war itself, the ugliness and monstrosity of it. Just as Toei’s Godzilla (1951) represents the threat of the atomic bomb with a hulking reptilian monstrosity that mindlessly destroys and crushes all in its wake, emerging from the murky depths to reduce Tokyo to rubble, “Mars” sounds like something ineffable, ephemeral, impossible to grasp — a beast emerging from the darkness, the hull of a warship emerging through the fog, the grimacing white teeth and eyes of a company of soldiers, set loose on a village filled with innocents…there is something simultaneously primal and sophisticated about this music. “Mars” is a profoundly ugly piece, brutal and terrifying in its attempt to sonically recreate the chaos of a battlefield. In many ways, “Mars” creates the feeling of listening to heavy metal, which is impressive for a piece written forty-five years before “Johnny B. Goode” (1958).

It is hard not to imagine “Mars” as being somewhat science-fictional in nature. It is possible that Holst was influenced by H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1897), though it is much more likely that Holst was inspired by the international war in Europe that was then-currently unfolding in his writing of the piece. However, it could just have easily been that he was imagining Roman centurions marching into battle, slaughtering and pillaging as they conquered. The piece features stabbing brass and pounding drums throughout that make it a very intense listen, including the occasional lull or rest, perhaps to fool the listener into believing the onslaught is at an end. Gradually the piece grows louder and louder and more aggressive, culminating in a crescendo of stabbing, explosive brass and percussion, ending one long, drawn out bass note, presumably to represent a sort of grim victory. The piece is followed by “Venus”, which is a far more soothing piece, featuring harps, strings, and lighter brass and percussion.

Within Star Wars, “Mars” has a number of influences. A piece from the opening of the film, titled “Imperial Attack”, plays as an Imperial Star Destroyer captures Princess Leia’s frigate, which is boarded by stormtroopers who proceed to murder her crew mercilessly, before Leia is finally taken into custody by the evil Darth Vader. The piece borrows several cues from “Mars”, including the stabs of brass and percussion and the fact it grows in intensity as the situation becomes more hopeless for our heroine.

“Mars” also makes an appearance towards the end of the film during the piece titled “The Battle of Yavin”, during which Luke, a relatively inexperienced pilot, is tasked with the extremely dangerous mission of destroying the Imperial superweapon, capable of destroying a planet, called the Death Star. Luke switches off his targeting computer to the shock of Leia and the other Rebel commanders, having been implored by his recently-deceased mentor Obi-wan to use The Force. As Luke draws closer and closer to the Death Star’s weak spot, the Imperial commanders below are preparing to fire the laser which will destroy the Rebel base, killing Leia and crushing the Rebellion for good. Mere seconds before the laser is fired, Luke fires his torpedoes, they fly into the exhaust port and into the Death Star’s core, instantly destroying it. Underscoring this thrilling climax (the culmination of which elicited cheers and applause from American audiences in 1977) are very Holst-esque stabs of brass and percussion, growing ever more intense as the Rebellion comes mere seconds away from destruction. Once again, the music used to represent the savagery and heartlessness of the Imperial military is used to represent their cold-blooded approach to rebellion and disobedience, but in this instance the heroes emerge – at least for now – triumphant. “The Battle of Yavin” is followed by pieces that sound quite similar to “Jupiter, The Bringer of Jollity” – fitting music for the jubilation felt by the characters and the audience at the end of the film in the face of their unlikely victory.

The most remarkable thing about The Planets is that it was never intended to be a soundtrack. We will probably never know what Holst was imagining while composing the piece. But it is interesting how the last century of popular culture has shaped our perception of the music. “Mars” was used as the theme for the British science fiction thriller The Quatermass Experiment (1953), and would also influence perhaps one of the most famous pieces of music from the Star Wars saga, “The Imperial March”, or “Darth Vader’s Theme”. Hans Zimmer also quoted “Mars” in his score for Gladiator (2000), perhaps fittingly for a film set in Ancient Rome. Even Nintendo have quoted “Mars” in their long-running Super Mario series of video games – the music used for the airship flown by Mario’s arch-nemesis Bowser, which originally appeared in Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988) but also makes appearances in Paper Mario (2000) and Super Mario Galaxy (2007) as well as the franchise’s most recent release, Super Mario Odyssey (2017), is very clearly based on “Mars”.

In short, it is now impossible to listen to “Mars” without imagining it to be some sort of soundtrack, despite the fact it was never intended as one. It is the music’s very influence on visual mass media that has made it almost synonymous with it in our minds.

It remains one of the most terrifying and exciting pieces of music ever composed and never fails to frighten and delight me in its brutal, awful majesty.

31 December 2020 @ 5:00 am

I think Holts’s Mars the Bringer of War captured the true horror of modern mechanized warfare.

Unlike the 19th century and before, were courage, skill of the professional soldiers mattered, the 20th century saw the rise of military industrial complex that brought the machine gun, tanks, conscripted soldiers turning warfare into a mass production death machine. The buildup to the climax of the piece captures the rhetoric and diplomacy leading up to the outbreak of chaos.